In this experimental first month of The Divine Perspective's existence, I've focused a lot on irrationality in politics. I've argued that our analytic lens for politics should be tinted by emotion, not policy preferences. I've linked to Larrie Ferreiro discussing the biological roots of our political behavior; our political beliefs tend to be rooted in our evolved disposition toward group interaction, not some rationalistic reflection on political philosophy. We've seen Jonah Lehrer observe that education doesn't reduce our tendency to fall victim to cognitive biases.

In short, I think our society tends to think about politics in overly rationalistic terms. We attempt to reduce social behavior to a simple link between aggregated personal preferences and group action. But politics doesn't actually work that way.

Ultimately, our ideological beliefs are thin props for our psychological predispositions toward political questions. This perspective may feel cynical (I have, after all, argued that lying holds a legitimate place in an irrational world), but I don't think it should feel that way.

We're comfortable acknowledging the centrality of feeling and emotion in our day to day life. We don't choose our favorite foods using some sort of flavor-calorie equation. We feel what's beautiful, fun, and moral; we don't deduce it. We don't choose a partner; we fall (the lack of conscious individual choice associated with falling being a vital part of the term) in love.

Yet we hesitate to admit the role of unconscious cognition in our political lives. Pseudo-intellectuals like me, who spend too much time thinking about politics and not enough thinking about real life, talk about things like median voter theory. We think about the products of preference and social processes without pausing to think about the source of the preferences or the nature of the processes.

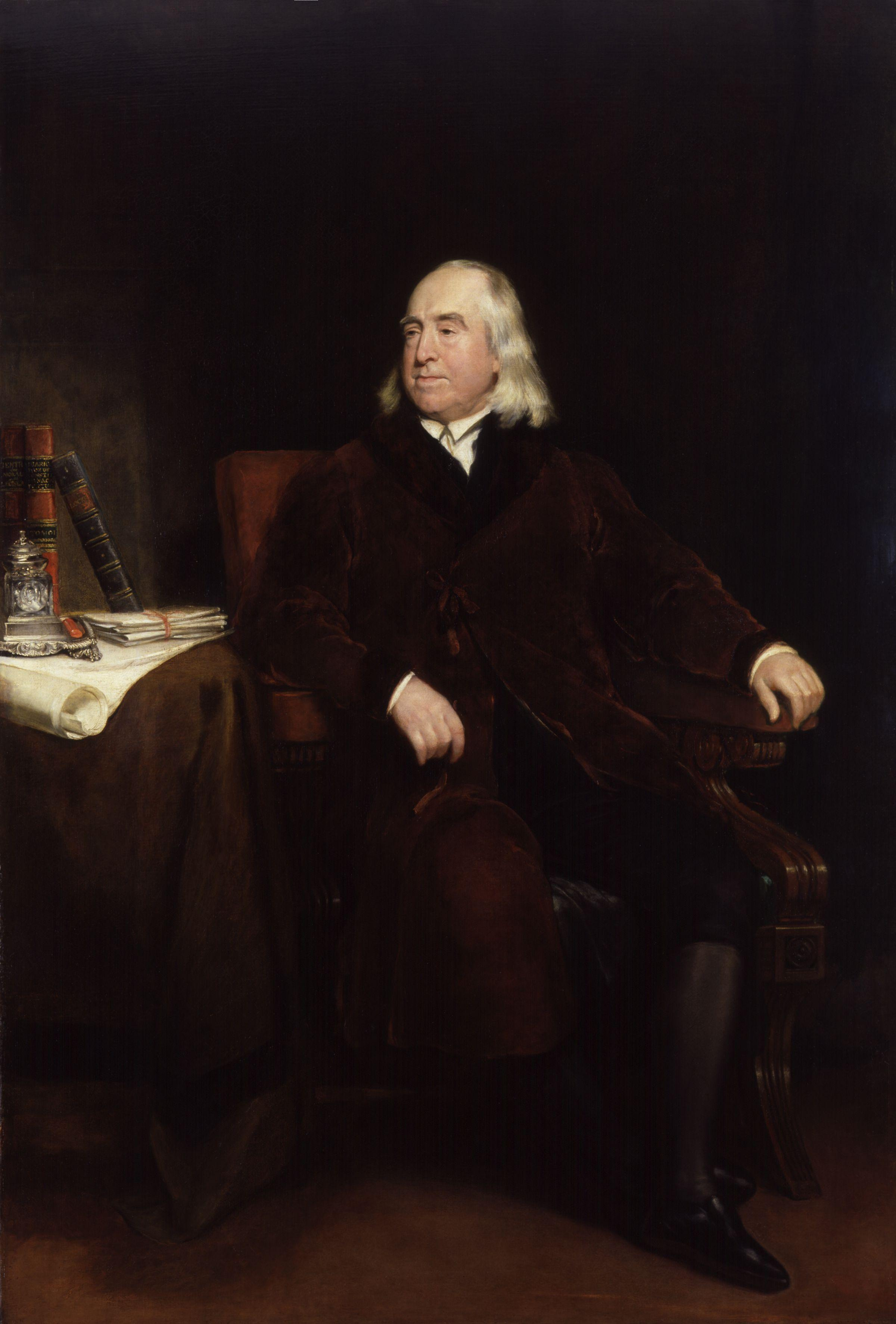

|

| Jeremy Bentham called abstractly derived rights "nonsense on stilts." I tend to agree. |

Lost in abstraction, we fail to recognize that, when it comes to politics, none of us know what the hell we're talking about most of the time. Even experts, after all, can't coalesce their knowledge into meaningfully accurate predictions most of the time.

Should our ignorance come as any surprise? Shouldn't the combined complexity of a global system, six billion brains strong, be expected to elude the comprehension of a single brain, a wave of the hand, and a tossed off ideological maxim?

Our ignorance, then, is nothing to be ashamed of. Nor is it something we can readily avoid.

We should acknowledge the limitations of our individual minds. But we should not abandon our tightly held beliefs or resort to apathy or boundless cynicism. Rather, we should treat our beliefs (whether political, moral, social, or religious) as perspective, not truths. We should treat our beliefs as malleable rather than static, mutable rather than timeless, contextual rather than abstract, fundamental but uncertain.

Faced with the limitations of our own cognition and the vast complexity of human social systems, our response cannot be arrogance, and should not be despair.

Our best response is humility.

|

| Humility. |

Later, I'll conclude this little essay with some thoughts on how republicanism (that's a small 'r') can help us integrate humility into our political reasoning.

No comments:

Post a Comment