Thursday, June 28, 2012

Blogging Hiatus

College friends coming in from out of town this weekend. No blogging (Nolan excepted) until Monday.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

The Fast and Furious Media Fails

|

| My solution: clone Bob Woodward. |

The fast and the furious scandal, allegedly centered on a botched ATF sting operation, has been the talk of the squabbling political class lately. The scandal has triggered a dispute over executive review and massive turmoil within the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

The right, predictably, has already come up with a parallel conspiracy theory: the Obama Administration let the guns into Mexico on purpose in order to foment more gun violence, in order to press their (yet to be exhibited in real life) crusade against the Second Amendment (and grandmas, and apple pie). I think it's worth noting that this wild theory is not only being propagated by loonies, but Darrell Issa, the chair of the relevant House Committee.

But even setting the conspiracy theory aside, there's a bigger problem: no "sting" ever happened.

The real sequence of events, per the Fortune (left wing rag?) investigation:

(1) ATF agents build a case against gun purchasers (apparently poor American kids) who work for Mexican drug cartels.

(2) Incredibly protective Arizona gun laws prohibit prosecutors from indicting even individuals who purchased hundreds of weapons in a sixth month span with cash. Guns that had been proven to pass into Mexico within weeks of their purchase.

(3) ATF agents, frustrated by the prosecutors' unwillingness to move on the case, determine that they can only prosecute if they allow the guns to move, track them, and survey the actual transfer of weapons. They write a memo to this effect.

(4) Not all weapons are successfully tracked. Some make their way to Mexico. And so on.

(5) Pissed off ATF agent leaks memo to press. Widespread outrage. Conservative blogs pick up the story. CBS picks up the story (this isn't a pure tale of "silly right wing media," by any means). Fox News decides to turn the story into the center of its news coverage for weeks.

(6) The Obama Administration, hesitant to engage in a fight over gun rights during an election year, rolls over.

There's lots of blame to go around. We could blame political hacks for engaging in a baseless witch hunt. We could blame President Obama (his concept of executive power seems to be "speak eloquently and bury your big stick"). We could blame America's insanely lax gun laws for allowing this sort of tragedy to occur in the first place.

But, ultimately, there will always be political hacks determined to create outrage from the ether. Presidents will always be overly sensitive to election year politics. And our messy democracy will produce messy laws that imprecisely navigate the hazy territory between civil liberties and good governance.

A passing untruth didn't became a national scandal because a pissed off DEA agent leaked a memo. It didn't become a national scandal because a hack Congressman decided to make it one. It didn't become a national scandal because Obama refused to do battle.

It became a national scandal because the national media allowed it to.

It's too easy to blame "the media." Both sides of the political spectrum do it all the time. But we can surely blame political journalism for allowing basic untruths to spread unabated. And for not calling the propagators of such untruths to account.

Journalism has the power to shape national political narratives. Journalism has the power to decide which accusations merit a story and which merit a fast track to the National Enquirer. Sometimes, in order to decide such merits, journalists will be required to (gasp!) investigate the veracity of a claim.

All too often, mainstream journalists simply provide quotes from a token member of each party and move on. They act as reporters, but rarely investigators, human microphones, but rarely human analysts. Mainstream political journalism has devolved, as Jonathan Chait has argued, into a sort of third party opposition research service.

We all know how the world works. The stories on Obama's conspiracy, or the failed "sting," or executive privilege claim, will garner thousands of re-tweets and Facebook shares. Behold the righteous indignation of the digital masses in comment streams and forums!

And quietly, somewhere in back page newspaper retractions, comparatively un-shared long form journalism investigations, and rarely read House Committee reports, the truth will stand, apparent but unnoticed.

I'll end with some contrasting Thomas Jefferson quotes:

The man who reads nothing at all is better educated than the man who reads nothing but newspapers.And yet:

Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

No Daily Reads Today

No daily reading today. Working on a few longer pieces that are eating more time than I hoped.

Go read Wonkblog or The Daily Dish or something.

Go read Wonkblog or The Daily Dish or something.

Monday, June 25, 2012

(Massive) Daily Reading: June 25, 2012

Sunday, June 24, 2012

Pat Nolan's Comparative Journalism Hour: Morsi Election Edition

Today we’ll look at how the international media has been

reacting to the election of Mohammed Morsi (“Mursi” in the Arabic media) as

Egypt’s first democratic president. He was affiliated with the Muslim

Brotherhood. Since the announcement, three distinct perspectives have emerged:

those coming from Egypt itself, those coming from the wider Middle East, and

those coming from the West. My English-language bias prevents me from viewing

some of the wider, particularly Eastern, perspectives. The bias, one of

selection, also provides me with a skewed view of Middle Eastern and Egyptian

reporting—where English journalism typically favors a secular (non-Islamist)

perspective.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Abbreviated Friday Reads: June 22, 2012

Jonathan Bernstein has a meandering and wonderful post on the Veepstakes and navigating the difficult ground between aggregate social "behavior" and individual "action":

This turns to be a fairly important point. It's a subject that Hannah Arendt wrote about long ago when she presented the contrast between "behavior" and action, in which behavior is defined as conforming to larger historical laws or trends (see The Human Condition, especially 41-45).

When we talk about politics, we need to somehow keep both things in mind, simultaneously. On the one hand, people do "behave" all the time, in theoretically perfectly predictable ways. I know that an overwhelming percentage of African American voters will support Barack Obama this November, and that an overwhelming percentage of LDS voters will back Mitt Romney, and there's nothing wrong with me "predicting" that, just as there's nothing wrong with predicting that Veepstakes isn't likely to affect voter choices. Just to emphasize (given what Williamson said), that has nothing at all to do with how well-informed or ignorant voters might be -- well-informed voters, overall, are somewhat more predictable than ignorant voters (because they're more likely to be solid partisans).

And yet. Action is always possible. Choice is always possible. Action, as Arendt argues, is as unpredictable as behavior is predictable. Of course it is not without influences, but it involves deliberate choice.Ezra Klein is on a vital tangent lately, criticizing the practice of contemporary political media:

As New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait wrote, “It’s obviously true that political campaigns will take their opponents’ statements out of context. That is probably unavoidable. The key step I’m focusing on here is when the journalist internalizes the work of the oppo researcher. Perhaps, in the end, the dumbest, least fair, most context-free interpretation of the line will ultimately prevail. But when journalists assume this will happen and make no effort to fight against that process, we go from merely reporting on the stupidity of politics to becoming accomplices of it.”

We also reduce the amount of useful information politicians offer to the public, making our jobs harder in the long term. What Obama no doubt learned from his “gaffe” news conference is that he shouldn’t do many news conferences. The downside risk of a poorly phrased, extemporaneous comment vastly outweighs the likelihood that whatever serious message he seeks to convey will make it through the media’s filter. What Romney learned from Obama’s news conference is that, if he’s lucky enough to become president, he shouldn’t do many news conferences, either. The sad part is, both politicians probably learned the right lesson — at least for their purposes.

Yglesias tries to reclaim the word "privatizing" from the right.

More neat stuff from Wonkblog. Sarah K provides a great chart on "how we die."

Thursday, June 21, 2012

Santucci's Unpretentious Blogging Capital: An Intro to Heterodox Economics

Josh Divine asked me to write about "5 Things Everyone Should

Know about radical economics, How Economics Departments Lie to College

Freshmen, Forgotten Insights from Marx, 5 Vital lessons from forgotten

economists, whatever," but I want to talk about art for a minute first.

It turns out this is a thing:

I think it's very modern in an unusual way. I think it's modern

mainly because it looks at the past and says things like "now a major

motion picture." I think it's modern because it looks at the past and says

"we should write our own ideas of cultural ascendancy onto this

Thing." Congratulations, Guy de Maupassant; you've made it.

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

Pat Nolan's Euro-Crisis Primer: Part One of Three

Economic dispatches

out of Europe often include the invocation of gravity: unity “teeters,” banks

“hang,” ratings “drop,” and currencies “float,” for now at least. Relative to

its prior trajectory, the continent is not faring well.

Histories of the crisis

are constantly popping up, often appearing as 1,200-word articles in elite

semi-specialized geopolitical or economic news weeklies. It’s worse when

they’re dangling blog posts. The histories usually attempt to posit one of many

theories of causation, it makes the authors feel as if, “hey, I’m contributing

to the solution by putting to stone a warning for future generations.” The

authors often feel obliged to tack on a section on what they would do to fix

things.

I’ll follow suit: the

European Debt Crisis was caused by a combination of poor foresight and even

worse oversight.

[This post, on poor foresight or the structural causes of

the European crisis, will be the first of three. The second will cover poor

oversight, and the third will offer that ever-tacky “fix.”]

Daily Reading: June 20, 2012

Today's best from around the web. [The awesome graphic, courtesy The Atlantic is from today's "must read." Click to enlarge. ]

If you read anything today, read this:

This brief economic history of the world, from The Atlantic, is bursting at the seams with great graphs.

Read these too:

Mulligan (NYT Economix) on Microsoft's fickle monopoly.

Coates has a two part piece (here's one, here's two) on racism in modern conservatism. Sensitive topic, I know, but Coates is one of the best, most nuanced writers on race out there today.

Nate Silver runs through possible electoral effects of Obama's big immigration move.

Suzy Khimm on Olympia Snowe's pre-retirement effort to address filibuster abuse. Good for you Senator Snowe. But to get any traction on filibuster reform we'll need someone with, you know, actual power to take up the cause .

Ezra Klein: the GOP has a history of moderation when it comes to the federal welfare state. Or at least a history of "motivated reasoning."

Apparently a lot of the stuff wine snobs throw around is...made up. I'll let honorary Divine Perspective trustee George Costanza handle this one:

If you read anything today, read this:

This brief economic history of the world, from The Atlantic, is bursting at the seams with great graphs.

Read these too:

Mulligan (NYT Economix) on Microsoft's fickle monopoly.

Coates has a two part piece (here's one, here's two) on racism in modern conservatism. Sensitive topic, I know, but Coates is one of the best, most nuanced writers on race out there today.

Nate Silver runs through possible electoral effects of Obama's big immigration move.

Suzy Khimm on Olympia Snowe's pre-retirement effort to address filibuster abuse. Good for you Senator Snowe. But to get any traction on filibuster reform we'll need someone with, you know, actual power to take up the cause .

Ezra Klein: the GOP has a history of moderation when it comes to the federal welfare state. Or at least a history of "motivated reasoning."

Apparently a lot of the stuff wine snobs throw around is...made up. I'll let honorary Divine Perspective trustee George Costanza handle this one:

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

Conservative Rhetoric, Liberal Lion? FDR's Commonwealth Club Address

Yesterday, I looked at Obama's recent economy address in Ohio. I claimed that the speech (along with most of Obama's rhetoric) fails to create a morally compelling vision of liberalism (even as it successfully frames Obama as a mature, moderate politician).

So who can create a broadly appealing vision of liberalism? FDR, of course.

I should note that Roosevelt, unlike Obama, didn't have a big role in writing his own speeches. But it's a common trope in American political analysis to say "Roosevelt," or "Reagan," or whoever, when we really mean "the team of advisers and communications professionals associated with Roosevelt/Reagan/whoever." So I'll just go with it.

My first (and only) speech-writing axiom: refuse to concede a single universally appealing moral good . If someone calls your foreign policy "weak," don't reply "my foreign policy is smart." Instead redefine strength so that it fits you own foreign policy. If someone calls your welfare policy "un-compassionate" redefine "compassion." And so on.

Roosevelt (or someone on his team) was a master of this approach, as was Reagan. Roosevelt's liberalism is strong and disciplined. Reagan presents conservatism with a compassionate, loving face.

I'll bloviate a bit on Reagan's rhetoric in the coming days (worth noting that Reagan voted for Roosevelt all four times).

For now, let's see how FDR does it, after the jump. I'm using his famous "Address to the Commonwealth Club."

Monday, June 18, 2012

Daily Reading: June 18, 2012

[Forgive the font-spacing issues. Having trouble with blogger's interface.]

If you read anything today, read this:

Franck Rich, one of the best stylists out there, issues a sweeping defense of negative political ads and suggests that Romney may be particularly vulnerable:

Ezra Klein uses the legislative history of the DREAM Act to suggest that compromising with the modern GOP is, well, impossible.

Dan Amira with some amusing snark about Obama's selection of John Kerry to impersonate Romney in debate prep. The two may have more in common than Massachusetts and gobs of money: perfect political resumes, limited campaigning skills.

Kevin Drum thinks a SCOTUS beat down of Obamacare would change American politics:

Read these if you have the time (a bit longer, but good):

Great reporting here, courtesy WaPo. How an untruth spreads in the modern media:

Doubling up on Ezra and SCOTUS links today. Klein gets to go all long form in The New Yorker, telling us how the indiviudal mandate went from completely non-controversial to politically toxic:

If you read anything today, read this:

Franck Rich, one of the best stylists out there, issues a sweeping defense of negative political ads and suggests that Romney may be particularly vulnerable:

The president, any president, should go negative early, often, and without apology if the goal is victory. The notion that negative campaigning is some toxic modern aberration in American democracy is bogus. No campaign may ever top the Andrew Jackson–John Quincy Adams race of 1828, in which Jackson was accused of murder, drunkenness, cockfighting, slave-trading, and, most delicious of all, cannibalism. His wife and his mother, for good measure, were branded a bigamist and a whore, respectively. (Jackson won nonetheless.) In the last national campaign before the advent of political television ads, lovable Harry Truman didn’t just give hell to the “do nothing” Congress, as roseate memory has it. In a major speech in Chicago in late October 1948, he revisited still-raw World War II memories to imply that the “powerful reactionary forces which are silently undermining our democratic institutions”—that would be the Republicans— and their chosen front man, Thomas Dewey, were analogous to the Nazis and Hitler. Over-the-top? Dewey was a liberal by the standards of the postwar GOP and had more in common with a department-store mannequin than with a Fascist dictator.No excuse to not read these (short but good):

Ezra Klein uses the legislative history of the DREAM Act to suggest that compromising with the modern GOP is, well, impossible.

Dan Amira with some amusing snark about Obama's selection of John Kerry to impersonate Romney in debate prep. The two may have more in common than Massachusetts and gobs of money: perfect political resumes, limited campaigning skills.

Kevin Drum thinks a SCOTUS beat down of Obamacare would change American politics:

If the court does overturn the mandate, it's going to be hard to know how to react. It's been more than 75 years since the Supreme Court overturned a piece of legislation as big as ACA, and I can't think of any example of the court overturning landmark legislation this big based on a principle as flimsy and manufactured as activity vs. inactivity. When the court overturned the NRA in 1935, it was a shock—but it was also a unanimous decision and, despite FDR's pique, not really a surprising ruling given existing precedent. Overturning ACA would be a whole different kind of game changer. It would mean that the Supreme Court had officially entered an era where they were frankly willing to overturn liberal legislation just because they don't like it. Pile that on top of Bush v. Gore and Citizens United and you have a Supreme Court that's pretty explicitly chosen up sides in American electoral politics. This would be, in no uncertain terms, no longer business as usual.

Read these if you have the time (a bit longer, but good):

Great reporting here, courtesy WaPo. How an untruth spreads in the modern media:

It was a blood-boiler of a story, a menacing tale of government gone too far: TheEnvironmental Protection Agency was spying on Midwestern farmers with the same aerial “drones” used to kill terrorists overseas.

This month, the idea has been repeated in TV segments, on multiple blogs and by at least four congressmen. The only trouble is, it isn’t true.

It was never true. The EPA isn’t using drone aircraft — in the Midwest or anywhere else.

The hubbub over nonexistent drones provides a look at something hard to capture in American politics: the vibrant, almost viral, life cycle of a falsehood. This one seems to have been born less than three weeks ago, in tweets and blog posts that twisted the details of a real news story about EPA inspectors flying in small planes.

Doubling up on Ezra and SCOTUS links today. Klein gets to go all long form in The New Yorker, telling us how the indiviudal mandate went from completely non-controversial to politically toxic:

On March 23, 2010, the day that President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act into law, fourteen state attorneys general filed suit against the law’s requirement that most Americans purchase health insurance, on the ground that it was unconstitutional. It was hard to find a law professor in the country who took them seriously. “The argument about constitutionality is, if not frivolous, close to it,” Sanford Levinson, a University of Texas law-school professor, told the McClatchy newspapers. Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the law school at the University of California at Irvine, told the Times, “There is no case law, post 1937, that would support an individual’s right not to buy health care if the government wants to mandate it.” Orin Kerr, a George Washington University professor who had clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy, said, “There is a less than one-per-cent chance that the courts will invalidate the individual mandate.” Today, as the Supreme Court prepares to hand down its decision on the law, Kerr puts the chance that it will overturn the mandate—almost certainly on a party-line vote—at closer to “fifty-fifty.” The Republicans have made the individual mandate the element most likely to undo the President’s health-care law. The irony is that the Democrats adopted it in the first place because they thought that it would help them secure conservative support. It had, after all, been at the heart of Republican health-care reforms for two decades.Do I have an altar to Ezra Klein in my basement? Maybe, maybe not.

I Love the Smell of Rhetorical Analysis in the Morning: Obama's Economy Speech

For several days now I've promised an analysis of Obama's big economy speech from last week. The text of the speech is available here.

Blogosphere reactions to the speech have been mixed.

Andrew Sullivan loved it:

My bottom line? A home run. Simply constructed, carefully reframed, aggressive while positive: the Obamaites have been listening to critics and are responding. If this is his message, and if he is able to keep articulating it this clearly, he will win. And in my view, the experience of the last thirty years is that he should win. If I have to choose between a governing philosophy espoused by Bill Clinton or one espoused by George W. Bush, it's a no-brainer. And I can't stand Bill Clinton.Ezra Klein, who frequently reminds us that individual speeches don't actually matter, likes the underlying strategy:

One speech doesn’t change an election, and this one won’t, either. But the Obama campaign’s line of attack does point to a difficulty for the Romney campaign in the coming months: Where can they show a sharp break with the policies of the Bush administration? Spending cuts, perhaps, but the more specific they get on what they’ll cut, the most voter opposition they face. When Lanhee Chen, the Romney campaign’s policy director, was asked this question on Bloomberg, he replied by noting Romney’s more confrontational attitude toward China. But voters may want more than that.Sullivan also rounded up some of the less favorable reactions.

I'd like to make a few preliminary points before diving in.

Sunday, June 17, 2012

Pat Nolan's International Conference Hour

Latin America is making headlines this June as heads of

state and finance officials book two-stop trips between Rio de Janiero, Brazil and

Los Cabos, Mexico. The first is ecological, and the second economic. The

occasions are similar in their international weight (external affairs

departments and ministries are in full-swing), but different in the immediacy.

Rio +20 is all about the long term Development buzzword “sustainability,” and

the G-20 summit is all about how to deal with the pressing matter of the

European crisis.

First Rio, then Cabos.

Friday, June 15, 2012

Abbreviated Daily Reading: June 15, 2012

It's a St. Louis Brewers' Heritage Festival kind of Daily Reading (meaning a short Daily Reading)

Sometimes, after all, I do things besides reading online news. Like drinking fine micro-brews from every corner of the greatest city on earth. [My favorite.]

A rhetorical analysis of Obama's economy address is coming tomorrow, with the second edition of Pat Nolan's Comparative Journalism Hour on tap for Sunday.

But still a lot of good stuff today:

Sometimes, after all, I do things besides reading online news. Like drinking fine micro-brews from every corner of the greatest city on earth. [My favorite.]

A rhetorical analysis of Obama's economy address is coming tomorrow, with the second edition of Pat Nolan's Comparative Journalism Hour on tap for Sunday.

But still a lot of good stuff today:

Thursday, June 14, 2012

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Left is Left, Right is Right: The Emotional Political Spectrum, Part III

Over the past few days I've claimed that our political beliefs are not based on rationally-derived policy preferences, but rather on moral worldviews--on our emotional preconceptions about the world. I proceeded to abstract these worldviews into less metaphorical statements of cognitive preference:

- The right prefers moral systems with statically defined, objective rules.

- The left prefers moral systems with dynamically defined, subjective rules.

I'd like to conclude these introductory posts on emotional politics by evaluating the potential benefits and pitfalls of each approach.

In Moral Politics, George Lakoff spends the final third of the book developing his argument for the superiority of the left's "Nurturant Mother" ideal. Lakoff founds his final argument on evidence that a nurturant worldview is rooted in a more empirically accurate account of human behavior. He may be right, but I think his approach risks getting lost in the details of his own metaphor.

I won't make a similar attempt here.

But I would like to spend a little time discussing what kind of thinking these different approaches will tend to generate. Let's start with the left.

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Daily Reading: June 12, 2012

If you read anything today, read this:

A new issue of the always-great Democracy: A Journal of Ideas is out today. The whole thing is worth reading, but I'll go with E.J. Dionne's sweeping case for reasserting a progressive vision of American history:

(1.) Weissmann runs through a worst case scenario for a Euro-zone meltdown. Bad, very bad. Really bad.

(2.) More Eurozone pessimism from Andrew Ross Sorkin.

(3.) I'll keep beating the irrationality drum. Great little piece on intelligence and cognitive bias:

(4.) Ezra reacts to Lizza (linked in yesterday's "Daily Reading") and reminds us that Congress, you know, matters:

(5.) David Brooks examines contemporary American political monuments and determines that we've forgotten how to think about just authority:

Chait follows up here.

(7.) Via Matt Yglesias, nice bit from Seth Stevenson on how Southwest has managed to say profitable in an unprofitable industry.

Read these if you have the time (a little longer, but good):

(1.) Walt: what makes a good ally? A realist's answer.

(2.) I'll double dip on Lehrer today. Why we don't trust science.

A new issue of the always-great Democracy: A Journal of Ideas is out today. The whole thing is worth reading, but I'll go with E.J. Dionne's sweeping case for reasserting a progressive vision of American history:

The Founders of our nation were daring, but they were also balanced, moderate, and temperate. They had confidence that government could be made to work and that it could accomplish great things, but they were always wary of deifying the state and those who ran it. They hugely valued individual freedom but were steeped in principles that saw the preservation of freedom as a common enterprise. They were influenced by the Bible and the Enlightenment, by liberalism and republicanism.No excuse not to read these (short but good):

(1.) Weissmann runs through a worst case scenario for a Euro-zone meltdown. Bad, very bad. Really bad.

(2.) More Eurozone pessimism from Andrew Ross Sorkin.

(3.) I'll keep beating the irrationality drum. Great little piece on intelligence and cognitive bias:

And here’s the upsetting punch line: intelligence seems to make things worse. The scientists gave the students four measures of “cognitive sophistication.” As they report in the paper, all four of the measures showed positive correlations, “indicating that more cognitively sophisticated participants showed larger bias blind spots.” This trend held for many of the specific biases, indicating that smarter people (at least as measured by S.A.T. scores) and those more likely to engage in deliberation were slightly more vulnerable to common mental mistakes.

(4.) Ezra reacts to Lizza (linked in yesterday's "Daily Reading") and reminds us that Congress, you know, matters:

Lizza, by the way, gets at much of this in his piece, so the post shouldn’t be taken as a critique of him. And don’t get me wrong: The president is powerful, and Congress is frequently reactive to the agenda he sets, so articles about what he wants to do are definitely worth reading. But there’s a huge imbalance in how much time the media — myself included — spend reporting on the executive branch vs. the legislative branch, and while that imbalance exists for perfectly understandable reasons, it leads readers to overestimate the importance of the president’s personal preferences and underestimate the importance of Congress.

(5.) David Brooks examines contemporary American political monuments and determines that we've forgotten how to think about just authority:

I don’t know if America has a leadership problem; it certainly has a followership problem. Vast majorities of Americans don’t trust their institutions. That’s not mostly because our institutions perform much worse than they did in 1925 and 1955, when they were widely trusted. It’s mostly because more people are cynical and like to pretend that they are better than everything else around them. Vanity has more to do with rising distrust than anything else.

In his memoir, “At Ease,” Eisenhower delivered the following advice: “Always try to associate yourself with and learn as much as you can from those who know more than you do, who do better than you, who see more clearly than you.” Ike slowly mastered the art of leadership by becoming a superb apprentice.(6.) Chait argues that Obama's "doing fine" gaffe may help him by re-focusing the debate on the realities of public sector employment:

But there are also ways in which the debate harms Romney. Seizing on Obama’s gaffe, Romney committed a counter-gaffe, in which he declared of Obama, “He says we need more firemen, more policemen, more teachers.” The flub here is one of excessive honesty. Americans may hate the idea of government in the abstract, but they like it in the specific. The Republican strategy is always to keep its discussion of government programs general — with a handful of exceptions, like foreign aid and programs that help the poor — while Democrats try to make it as specific as possible. Firing police officers, firefighters, and teachers is way less popular than firing government bureaucrats. Obama has taken great care to turn the question into one of those specific job categories, and Romney has inadvertently helped him.

Chait follows up here.

(7.) Via Matt Yglesias, nice bit from Seth Stevenson on how Southwest has managed to say profitable in an unprofitable industry.

Read these if you have the time (a little longer, but good):

(1.) Walt: what makes a good ally? A realist's answer.

(2.) I'll double dip on Lehrer today. Why we don't trust science.

Left is Left, Right is Right: The Emotional Political Spectrum, Part II

Yesterday, I argued that rational justifications for our political beliefs are ultimately pretensions, stand-ins for deeper cognitive processes.

But if our policy preferences are mostly superficial, which factors are fundamental? Where do our political beliefs ultimately find their roots?

I'm going to draw on George Lakoff to suggest an answer to this question and provide my claims with a thin veneer of intellectual legitimacy. Folks interested in political psychology should read his books. The Political Mind and Moral Politics are both great, very accessible reads. There's a decent, free .pdf version of his ideas (though more oriented toward lefty political strategists) in Thinking Points.

Lakoff is a linguist by trade; his approach to political psychology is founded on his work in cognitive linguistics. But for now I'll ignore his (vital and fascinating) points on language to focus on the moral perspectives which he argues underpin our political life.

He identifies two basic moral worldviews: a "strict father" (righty) model and a "nurturant parent" (lefty) model. He recognizes that most individuals don't employ a unitary version of either moral system. Just as few of us are "pure" liberals or conservatives, few of us operate under the same moral assumptions in every situation. But it's still useful to articulate each system in starkly divergent terms. I'll let a few quotes from Moral Politics do the heavy lifting:

The Strict Father

"The Strict Father model takes as background the view that life is difficult and the world is fundamentally dangerous....Survival is a major concern and there are dangers and evils lurking everywhere, especially in the human soul....[The father] teaches children right from wrong by setting strict rules for their behavior and enforcing them through punishment. The punishment is typically mild to moderate, but sufficiently painful....He also gains their cooperation by showing love and appreciation when they do follow the rules. But children must never be coddled, lest they become spoiled; a spoiled child will be dependent for life and will not learn proper morals....Self-discipline, self-reliance, and respect for legitimate authority are the crucial things a child must learn. A mature adult becomes self-reliant through applying self-discipline in pursuing his self-interest. Only if a child learns self-discipline can he become self-reliant later in life. Survival is a matter of competition, and only through self-discipline can a child learn to compete successfully."The Nurturant Parent

"The primal experience behind this model is one of being cared for and cared about, having one's desires for loving interactions met, living as happily as possible, and deriving meaning from mutual interaction and care. Children develop best through their positive relationships to others, through their contribution to their community, and through the ways in which they realize potential and find joy in life....The principal goal of nurturance is for children to be fulfilled and happy in their lives and to become nurturant themselves. A fulfilling life is assumed to be, in significant part, a nurturant life, one committed to family and community responsibility. Self-fulfillment and the nurturance of others are seen as inseparable. What children need to learn most is empathy for others, the capacity for nurturance, cooperation, and the maintenance of social ties...Raising a child to be fulfilled also requires helping that child develop his or her potential for achievement and enjoyment."Lakoff's linguistic work centers on metaphorical cognition, but for our purposes there's no reason to get caught up in the details of his parent metaphor (though it's hard not to think of the deviant right's fascist "Fatherland" and the deviant left's Stalinist "Motherland"). The point here is that we find certain personal values embodied in conservative thinking: discipline, self-reliance, and incentive based behavior. We find other personal values embodied in liberal thinking: empathy, self-actualization, and socially rooted behavior.

Superficially, these models don't offer us a lot of help in justifying the traditional left-right political scale. Libertarians, traditional members of the right, hardly envision the state as a strict father. And we cannot fairly classify totalitarian leftist regimes as "nurturing mothers." But the whole point of this brand of political psychology is to think about the implicit cognitive assumptions of different ideologies, not their explicit manifestations, to think about political beliefs with a humanist, literary tool-set first, and a social science, empirical tool-set second. Sometimes we should focus on the emotional content of an idea rather than its most apparent practical manifestations.

But we don't always have the time or inclination to think about political beliefs as we would think about literature. So let me zoom out from George's metaphor and propose a more abstract (and scientifically baseless) distinction: the right prefers moral systems with statically defined, objective rules. The left prefers moral systems with dynamically defined, subjective rules.

My formulation is probably so abstract as to be meaningless, so let's dive in.

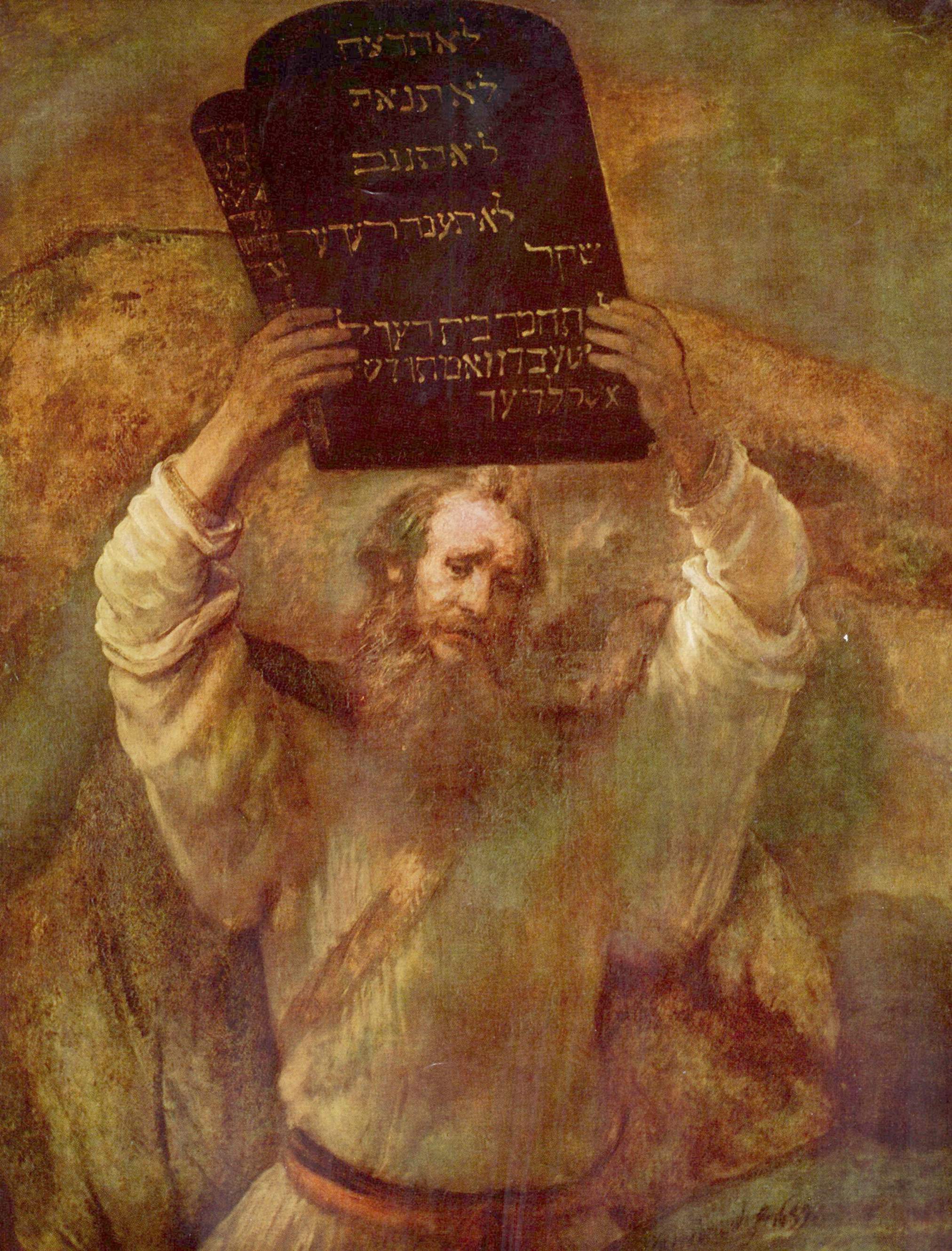

[Caveat: I'm a down-the-line liberal, but I don't see either approach to morality as obviously superior. Both have strengths and weaknesses, which I'll discuss tomorrow. The graphics provide a pseudo-intellectual suggestion that the Ten Commandments and Beatitudes constitute a parallel moral contrast in the Christian tradition.]

The right prefers moral systems with statically defined, objective rules.

These rules are defined a priori in one way or another, and are then used to develop a moral system with impressive internal coherence. A moral worldview founded on authority, after all, needs an objective source of authority.

Take the religious right: the word of God is an objective good; society should be organized to create a society that embodies the word of God.

The conservative tradition of Burke is less comfortable assuming the rectitude of a precise theological vision, but wants to deliberately value the accumulated wisdom of humanity (as embodied in tradition) over the transient (subjective) abstractions of societal reformers. For Burkean conservatives, tradition functions as an objective moral anchor which society should order itself on. Society should be structured to allow tradition to function as a ballast against unnecessary social change.

Using this mode of thought, we can also neatly fold libertarians into the right. Libertarians like to define a certain set of rights as objectively "natural" and build a moral system founded on the protection of these rights (in a notable tie to mainstream conservatism, these rights were originally defined religiously). These natural rights function as objective societal goods. Libertarians are dismissive of societal attempts to define additional rights; such attempts are subjective and therefore illegitimate. Government can legitimately act to protect the rights defined as "natural," but additional state action is correspondingly illegitimate. Even the hardcore Rothbard types fit in nicely: the fatal flaw of government is its lack of exposure to free market discipline.

To echo Lakoff's metaphor, "father" doesn't have to be government. The source of discipline may be God or the marketplace. But some form of discipline matters. And this discipline requires roots in some sort of objective truth.

The left prefers moral systems with dynamically defined, subjective rules.

These rules are humanly defined; they are truths only relative to the historical moment and thus ever changing.

The left's moral rhetoric is more likely to echo the Utilitarian or Pragmatic traditions, traditions which define truth as socially embedded rather than objectively evident. Members of the left tend to be more comfortable allowing some putative embodiment of "the people" (whether a legislature or Politburo) to define social truths. The left sometimes believes in "rights," but sees them as rules afforded some heightened level of societal protection, not objectively derived truths (Bentham, after all, called rights "nonsense on stilts").

We can't divide the left into ideological camps so easily, because the left is less overtly ideological (a critic might say "unprincipled"). Rather than building a worldview on an objective standard, the left likes to jump into programs of social improvement, ultimately confident that mechanisms of social aggregation (often the government) will organize their efforts in a socially beneficial way. And so lefties jump into one nurturant project or another, projects ranging from saving the environment to uplifting the poor. We try to help some person or system self-actualize, costs (the market's purportedly objective measure of value) be damned.

To the extent that the left is divided into camps, it's through these projects: environmentalists, internationalists, educators, and welfare statists (that's me). Political beliefs tend to be focused on these discrete projects rather than objective social truths.

-----------------------

Tomorrow, I'll finish this introductory series on emotional politics by evaluating the potential benefits and pitfalls of each moral system.

Monday, June 11, 2012

Daily Reading: June 11, 2012

If you read anything today, read this:

Ryan Lizza's piece in The New Yorker on a second Obama term is the talk of the blogosphere today. Yes, it's long, but it's definitely worth your time. Some great historical commentary on second-term governance along with some great pontificating on the potential options for the Obama Administration.

This bit on Nixon's second term attempt to assert control over the federal bureaucracy is particularly haunting:

Nixon gave his aides detailed directions about how to flush unsympathetic bureaucrats from the government after he won reëlection. Early in the 1972 campaign, he wrote his aides with instructions for a “housecleaning” at the C.I.A.:

'I want a study made immediately as to how many people in CIA could be removed by presidential action. . . . Of course, the reduction in force should be accomplished solely on the ground of its being necessary for budget reasons, but you will both know the real reason. . . . I want you to quit recruiting from any of the Ivy League schools or any other universities where either the university president or the university faculties have taken action condemning our efforts to bring the war in Vietnam to an end.'No excuse to not read these (short but good):

(1.) At the always great NYT blog Economix, Polak and Schott highlight America's own version of austerity, an austerity driven by cuts in spending by local governments. I think the mainstream US media deserves some serious wrist-slapping for their treatment of American government spending during the Great Recession. Too many journalists allow their economic coverage to be driven by major, high-profile events (like the stimulus or the debt ceiling debate). The problem is that economic performance is driven by trends, not, typically, by major events. I'm not asking journalists to employ sophisticated economic theory, just to achieve some passing familiarity with actual data.

(2.) Over at Wonkblog, Brad Plumer provides a very readable breakdown of Euro-crisis response options.

(3.) I'm double dipping (deservedly!) Wonkblog today. Ezra Klein goes after Bobby Jindal and defends the Obama Administration's stance toward "business":

After taxes, corporate profits amounted to 6.9 percent of GDP in 2010 — their highest level since 1966. That’s not, by any means, the singular result of the Obama administration’s policies. But it’s happening amidst their policies. And it speaks to the underlying reality of this recovery: Corporate taxes are near all-time lows and corporate profits are near all-time highs. That’s a mighty odd outcome for an administration that supposedly sees the existence of private businesses as an unpleasant side effect of the government’s need for tax revenues, don’t you think?

(4.) Jonathan Chait destroys zombie arguments about gay marriage and parenting (shamey shamey Douhat).

(5.) Matt Yglesias talks Demorat tax cut strategy. It's a mystery to me why any Democratic strategists would believe they could successfully marshal public opinion against the GOP on anything, given the recent past and hazy connection between legislative reality and popular perception.

(6.) This election will likely focus on the economy. But Andrew Sullivan reminds us that the neocons are still breathing. And they have Romney's ear.

Read these if you have the time (long-ish but good):

(1.) Via Arts and Letters Daily, a fascinating account of family structure and inequality:

So the single-mother revolution has left us with the following reality. At the top of the social order is a positive feedback loop, with kids raised in stable, high-investment, and relatively affluent homes going to college, finding similar mates, and raising their own children in stable, high-investment, and relatively affluent homes. At the bottom is a negative feedback loop, with kids raised by single mothers in unstable, low-investment homes finding themselves unable to adapt to today’s economy and going on to create more unstable, single-mother homes.(2.) At The Atlantic Ferreiro reviews an evolutionary theory of political behavior. Fascinating stuff, in keeping with The Divine Perspective's recent (much clumsier) focus on political psychology:

Greatly simplified, his argument is that two rival evolutionary forces drive human behavior: first, individual selection, which rewards the fittest individuals by passing along their genes; and second, group selection, in which the communities that work best together come to dominate the gene pool. Wilson argues that these two evolutionary forces are at work simultaneously, so that both self-serving and altruistic behaviors are constantly competing at the individual and at the group level. As he explains, "Members of the same group compete with one another in a manner that leads to self-serving behavior .... At the higher level, groups compete with groups, favoring cooperative social traits among members of the same group." In other words, individuals with self-serving behaviors beat altruistic individuals, while groups of altruists beat groups of individuals with self-serving behaviors.

Time and Intensity in the Senate: Thinking About Institutional Functionality

[Image from the filibuster related Capra classic, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.]

Over at The Monkey Cage, which anyone interested in political science (and here I really mean political science, not politics) should read every day, Koger discusses an interesting proposal that "in lieu of the filibuster as a defense against tyranny of the majority, the Senate should allocate each senator a 'budget' of votes which they can allocate across proposals as they like, so each senator can 'spend' a lot of votes on proposals that s/he considers very important."

Here's Koger's interesting turn:

As a practical matter, the Senate already has something like this system in the form of legislators’ time. Each member of the Senate starts out with the same amount of time before the next election and similar legislative staff allocations (plus bonuses for committee chairs). Then each senator makes two allocation decisions: first, how much time will s/he spend legislating instead of fundraising, visiting the home state, or hanging out with the family? Second, how much legislative time will s/he allocate to each issue? If senators’ time & staff resources are limited and senators’ efforts influence whether a proposal succeeds or fails, then the allocation of time is an indirect form of measuring and incorporating preference intensity into the legislative process.

A few take-aways here. First, as Koger goes on to note in the rest of the post, the filibuster (as currently instituted) undermines this system by requiring a relatively low threshold of interest to prevent legislative action while requiring a slightly higher threshold to advance the same legislative action. The "classic" filibuster, while superficially quite similar, functioned differently because it required large time outlays from individual Senators to be maintained.

The broader takeaway is that the informal, cultural characteristics of institutions matter just as much as their more formal rules and structures. But we naturally tend to give a lot more weight to the superficial structure of institutions than the less obvious norms which define how institutions actually operate.

I'm not sure how global this tendency happens to be, but I suspect it's worse in the US. Here, the average person is probably exposed to about 5 days of political science in their life: the week spent on the Constitution in high school American history. A week, in other words, discussing the formal structure of checks and balances embedded in our founding institutional order. But no high school history class I've ever heard of goes further and examines how our structure of checks and balances actually functions. Do our checks successfully protect political minorities? Or do they simply act as governance choke-points easily manipulated by special interests with narrow but intense policy preferences?

And does a system with a bicameral legislature, a Presidential veto, a judiciary empowered with judicial review, and relatively robust local governance really need an additional minority protection embedded in the Senate rules?

Here's one thing we don't consider in high school civics: if one institutional checkpoint becomes tighter than the rest, the institution that controls it will only benefit. A check which curtails the Senate's ability to act (like the filibuster or the hold) ensures, ironically, that the Senate will be at the center of any major federal policy initiative.

For a Senator more interested in personal influence than efficient governance, the status quo looks just fine.

Left is Left, Right is Right: The Emotional Political Spectrum, Part I

Last week, I used Paul Krugman's commentary on Reagan-style Keynesianism to suggest that we don't actually think about politics in rational, policy-based terms. I'd like to flesh out that point, which I suspect will become a frequent one at The Divine Perspective.

I have a libertarian friend who always objects to having his kind categorized as part of the "Right." Fine, almost all my libertarian friends object to being put in the righty basket. They tend to prefer systems like The Political Compass that provide a dual-axis model of ideology:

To the extent that political behavior is founded on policy preferences, this sort of scheme obsoletes a traditional left-right spectrum. To the extent that politics is about models of governance, my libertarian-minded friends are right to object to the traditional spectrum; their ideal government looks strikingly different from a conservative or fascist regime.

So why has the traditional left-right model been the dominant popular tool for sorting ideology in the modern era (in fact ever since the French Revolution)?

My answer, simply stated: political behavior is founded on moral-emotional world views. Policy preferences are, most fundamentally, expressions of those world views. And the traditional left-right classification system adequately, if crudely, describes the psychological spectrum underlying the political spectrum.

Before I dive into the argument, I'd like to illustrate what I mean using an example stolen from one of my undergraduate political science professors . Let's think back to the Henry Louis Gates controversy from a few years ago.

When most of us heard the news about a black Harvard professor getting arrested for trying to break into his own home, we knew exactly what had happened.

Lefties like me knew how it went down: a racist cop responded to a racist telephone call; just another chapter in the history of pervasive cultural oppression of minorities. We likely knew it instantly upon seeing the headlines, still completely ignorant of the actual facts. I suspect that most righties summarily reached a different conclusion: another poor cop, just trying to do his job, was about to be forced to run the gauntlet of the politically correct liberal media choir. And once again, I'm willing to bet that most righty minded folks reached this conclusion before reading any of the actual facts.

By now I suspect that many readers (if there are any readers...) are bouncing around in their chairs, protesting: "But I waited to react to that controversy until I knew the facts. I read the news, thought about the situation, and came to rational, fair-minded judgement of the incident." And I'm sure many people did respond in a fair-minded way to the incident.

But the Gates incident is easier to fairly analyze than the vast majority of actual political issues. It's a situation we can all imagine with some accuracy: a man gets locked out of his house and starts being rough with the front door; a vigilant/nosy neighbor calls the police. This incident doesn't feature any tricky abstract ideas or require any particular expertise to decode. Let's think about more common political issues, issues steeped in complexity and far beyond the day to day experiences of the average citizen, issues like "the role of regulation in the economy."

Almost every politically minded person I know, lefty or righty, has some stridently held views on the state's role in the economy. And yet most liberals I know couldn't come close to articulating even the most fundamental explanations of why markets should be efficient in first place. And most righties I know are ignorant of even the most uncontroversial accounts of why markets can lapse into inefficiency.

We like to walk around pretending we have logically founded positions on the role of the state in economic regulation, but almost none of us do. We're kidding ourselves. Smart men spend decades studying price signals and market failures, and most of these smart men only barely understand what they're talking about. I'm a relatively high information voter in the scheme of things (I spend two or three hours a day reading about politics, policy, and economics), and I have no idea what the hell I'm talking about most of the time.

So how do we choose? If our empirical justifications for our political beliefs are superficial, why do we choose the justifications we do?

I'll address those questions in Part II, tomorrow.

Sunday, June 10, 2012

Pat Nolan's Comparative Journalism Hour

Welcome to Divine Perspective’s Sunday news comparison.

These weekly posts intend to subjectively conflate news

sources from around the world and across the spectra in order to bring you an

ill-informed media analysis of an event from the preceding week. Well, they

will do that every week but this one. Today I am looking at inaugural blog

posts.

While I’m not introducing this blog—Josh did it here—I

am introducing my contribution to this blog. It’s difficult for any number of

reasons. Part of me wants to put humility forward and avoid writing about

writing (there’s an adage out there). When I didn’t know how to kick it off, I

started looking to see what others did. I was hoping to find a correlation

between the style or etiquette on the one hand, and the content on the other.

Hot Air, Michelle Malkin’s conservative blogomerate, kicks

off with two structural

but manifesto-declaring posts that both identify their alignment to the

conservative cause and explain to readers how the site will function. It’s a

very human, social approach, but also unapologetically rhetorical. The

unqualified pronouncement is reminiscent of the right’s pop-journalism. Not

sure it would stand up over at the National Review.

Think Progress, blog of the leftist Center for American

Progress, preferred the

professional 0-60, throw the nonswimmer into the pool approach. There’s no

green light, no announcement. One minute there’s nothing but a browser’s “Page

Not Found,” and the next the blog has explained why Bush should certainly close

Guantanamo. Its use of argument form might be elitist. Its lack of introduction

might be anti-social.

Let’s jump scale and amplify the tone of these two

etiquette-content matchups to the national level. The right is dumb, but

admirable for taking social issues so personally. The left is smart, but lacks

the intuitive social skill-set that leadership mandates. Let me offer an

alternative.

Hu Shuli, Beijing’s mainstream but independent news-teller

extraordinaire, has her cake and eats it. Her clever move was to take the Think Progress quick

start (avoiding the writing about writing thing), but leverage that ignorance

of social protocol against her choice of content: how to surf the web. This

kind of thing is not her specialty (she’s a wonk), but it serves as a nod to

the above conundrum.

My implications aside, there is no connection between your

political orientation or your native country’s freedoms of expression and your

style of inaugural posting. Inaugural blog posts are not very

consequential—expect me on the Greek exit next week—but the points are that

creative solutions exist, that news is

entertainment, that self-deprecation can be an unfortunate necessity.

--By Pat Nolan

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_1988,_MiNr_826.jpg)

.djvu/page1-351px-Report_on_Manufactures_(Hamilton).djvu.jpg)

_-_James_Tissot.jpg)