Yesterday, I argued that rational justifications for our political beliefs are ultimately pretensions, stand-ins for deeper cognitive processes.

But if our policy preferences are mostly superficial, which factors are fundamental? Where do our political beliefs ultimately find their roots?

I'm going to draw on George Lakoff to suggest an answer to this question and provide my claims with a thin veneer of intellectual legitimacy. Folks interested in political psychology should read his books. The Political Mind and Moral Politics are both great, very accessible reads. There's a decent, free .pdf version of his ideas (though more oriented toward lefty political strategists) in Thinking Points.

Lakoff is a linguist by trade; his approach to political psychology is founded on his work in cognitive linguistics. But for now I'll ignore his (vital and fascinating) points on language to focus on the moral perspectives which he argues underpin our political life.

He identifies two basic moral worldviews: a "strict father" (righty) model and a "nurturant parent" (lefty) model. He recognizes that most individuals don't employ a unitary version of either moral system. Just as few of us are "pure" liberals or conservatives, few of us operate under the same moral assumptions in every situation. But it's still useful to articulate each system in starkly divergent terms. I'll let a few quotes from Moral Politics do the heavy lifting:

The Strict Father

"The Strict Father model takes as background the view that life is difficult and the world is fundamentally dangerous....Survival is a major concern and there are dangers and evils lurking everywhere, especially in the human soul....[The father] teaches children right from wrong by setting strict rules for their behavior and enforcing them through punishment. The punishment is typically mild to moderate, but sufficiently painful....He also gains their cooperation by showing love and appreciation when they do follow the rules. But children must never be coddled, lest they become spoiled; a spoiled child will be dependent for life and will not learn proper morals....Self-discipline, self-reliance, and respect for legitimate authority are the crucial things a child must learn. A mature adult becomes self-reliant through applying self-discipline in pursuing his self-interest. Only if a child learns self-discipline can he become self-reliant later in life. Survival is a matter of competition, and only through self-discipline can a child learn to compete successfully."The Nurturant Parent

"The primal experience behind this model is one of being cared for and cared about, having one's desires for loving interactions met, living as happily as possible, and deriving meaning from mutual interaction and care. Children develop best through their positive relationships to others, through their contribution to their community, and through the ways in which they realize potential and find joy in life....The principal goal of nurturance is for children to be fulfilled and happy in their lives and to become nurturant themselves. A fulfilling life is assumed to be, in significant part, a nurturant life, one committed to family and community responsibility. Self-fulfillment and the nurturance of others are seen as inseparable. What children need to learn most is empathy for others, the capacity for nurturance, cooperation, and the maintenance of social ties...Raising a child to be fulfilled also requires helping that child develop his or her potential for achievement and enjoyment."Lakoff's linguistic work centers on metaphorical cognition, but for our purposes there's no reason to get caught up in the details of his parent metaphor (though it's hard not to think of the deviant right's fascist "Fatherland" and the deviant left's Stalinist "Motherland"). The point here is that we find certain personal values embodied in conservative thinking: discipline, self-reliance, and incentive based behavior. We find other personal values embodied in liberal thinking: empathy, self-actualization, and socially rooted behavior.

Superficially, these models don't offer us a lot of help in justifying the traditional left-right political scale. Libertarians, traditional members of the right, hardly envision the state as a strict father. And we cannot fairly classify totalitarian leftist regimes as "nurturing mothers." But the whole point of this brand of political psychology is to think about the implicit cognitive assumptions of different ideologies, not their explicit manifestations, to think about political beliefs with a humanist, literary tool-set first, and a social science, empirical tool-set second. Sometimes we should focus on the emotional content of an idea rather than its most apparent practical manifestations.

But we don't always have the time or inclination to think about political beliefs as we would think about literature. So let me zoom out from George's metaphor and propose a more abstract (and scientifically baseless) distinction: the right prefers moral systems with statically defined, objective rules. The left prefers moral systems with dynamically defined, subjective rules.

My formulation is probably so abstract as to be meaningless, so let's dive in.

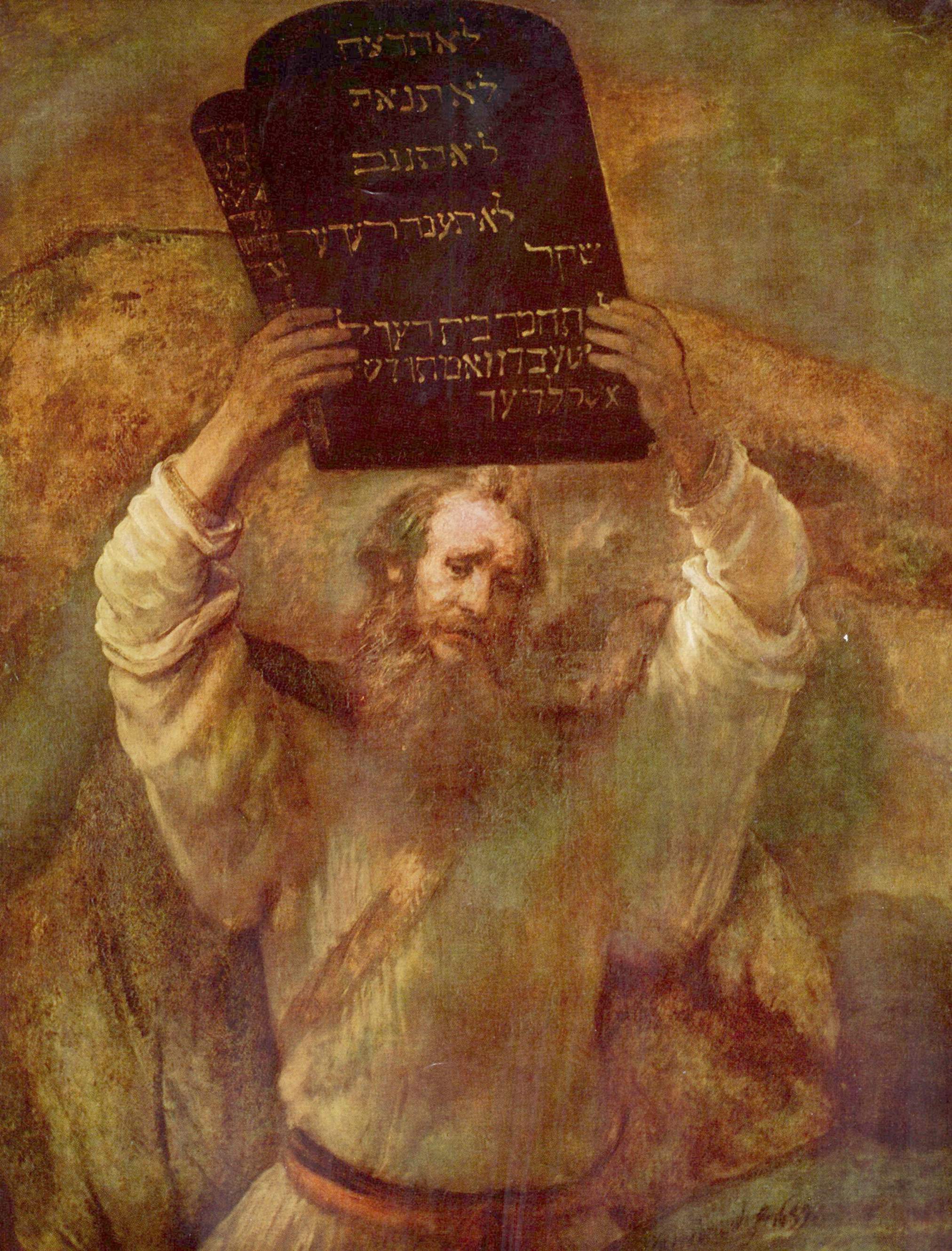

[Caveat: I'm a down-the-line liberal, but I don't see either approach to morality as obviously superior. Both have strengths and weaknesses, which I'll discuss tomorrow. The graphics provide a pseudo-intellectual suggestion that the Ten Commandments and Beatitudes constitute a parallel moral contrast in the Christian tradition.]

The right prefers moral systems with statically defined, objective rules.

These rules are defined a priori in one way or another, and are then used to develop a moral system with impressive internal coherence. A moral worldview founded on authority, after all, needs an objective source of authority.

Take the religious right: the word of God is an objective good; society should be organized to create a society that embodies the word of God.

The conservative tradition of Burke is less comfortable assuming the rectitude of a precise theological vision, but wants to deliberately value the accumulated wisdom of humanity (as embodied in tradition) over the transient (subjective) abstractions of societal reformers. For Burkean conservatives, tradition functions as an objective moral anchor which society should order itself on. Society should be structured to allow tradition to function as a ballast against unnecessary social change.

Using this mode of thought, we can also neatly fold libertarians into the right. Libertarians like to define a certain set of rights as objectively "natural" and build a moral system founded on the protection of these rights (in a notable tie to mainstream conservatism, these rights were originally defined religiously). These natural rights function as objective societal goods. Libertarians are dismissive of societal attempts to define additional rights; such attempts are subjective and therefore illegitimate. Government can legitimately act to protect the rights defined as "natural," but additional state action is correspondingly illegitimate. Even the hardcore Rothbard types fit in nicely: the fatal flaw of government is its lack of exposure to free market discipline.

To echo Lakoff's metaphor, "father" doesn't have to be government. The source of discipline may be God or the marketplace. But some form of discipline matters. And this discipline requires roots in some sort of objective truth.

The left prefers moral systems with dynamically defined, subjective rules.

These rules are humanly defined; they are truths only relative to the historical moment and thus ever changing.

The left's moral rhetoric is more likely to echo the Utilitarian or Pragmatic traditions, traditions which define truth as socially embedded rather than objectively evident. Members of the left tend to be more comfortable allowing some putative embodiment of "the people" (whether a legislature or Politburo) to define social truths. The left sometimes believes in "rights," but sees them as rules afforded some heightened level of societal protection, not objectively derived truths (Bentham, after all, called rights "nonsense on stilts").

We can't divide the left into ideological camps so easily, because the left is less overtly ideological (a critic might say "unprincipled"). Rather than building a worldview on an objective standard, the left likes to jump into programs of social improvement, ultimately confident that mechanisms of social aggregation (often the government) will organize their efforts in a socially beneficial way. And so lefties jump into one nurturant project or another, projects ranging from saving the environment to uplifting the poor. We try to help some person or system self-actualize, costs (the market's purportedly objective measure of value) be damned.

To the extent that the left is divided into camps, it's through these projects: environmentalists, internationalists, educators, and welfare statists (that's me). Political beliefs tend to be focused on these discrete projects rather than objective social truths.

-----------------------

Tomorrow, I'll finish this introductory series on emotional politics by evaluating the potential benefits and pitfalls of each moral system.

_-_James_Tissot.jpg)

Jonathan Haidt adds a lot to this topic in his book, The Righteous Mind, through his research on moral psychology and his Moral Foundations Theory. Like Lakoff, he discusses how our morality and emotions evolved through an interaction between individual level and group level selection. We come with 6 foundations from which we draw our morality, and how we think about each one determines much of our political leanings. For example, liberals prioritize the foundations derived from Care/Harm and Liberty/Oppression, while conservatives elevate other foundations, such as Authority/Subversion and Sanctity/Degradation.

ReplyDeleteI think his theory coincides nicely with what is presented here in regards to statically determined rules versus dynamically determined rules. Conservatives respect for the foundations of authority and loyalty leads them to have a strong desire to uphold the already existing rules and stick to traditions, while liberals are more likely to flaunt tradition if they see a better option.

He also has a mountain of very interesting research about how our minds make rapid emotional intuitive decisions, and only afterwards do we come up with rational justifications for our actions.

This is a great talk he gave summarizing the research that would lead to his book:

http://www.ted.com/talks/jonathan_haidt_on_the_moral_mind.html

Love Haidt! Though I haven't read his book.

ReplyDeleteDrew Westen has some solid stuff too, though he's pretty clumsy when he tries to turn his academic lens onto real politics.